Key Points

-

Provides insight into the training requirements of GDPs.

-

Increases understanding of the barriers to providing care to dentally anxious patients.

-

Helps educators develop specific training needs for GDPs.

Abstract

Background With regard to the management of dental anxiety in general dental practice, it has been considered that general dental practitioners (GDPs) are well placed to treat adults with mild forms of dental anxiety. However, little is known about the specific anxiety management techniques being used by GDPs in the UK.

Aim To determine the views and experiences of dental practitioners in their current use of anxiety management techniques, their undergraduate and post-graduation training in these techniques and future training needs.

Methods A postal questionnaire was sent to a sample of GDPs working in the Midlands region (n = 750) in the UK. Dentists were randomly selected using lists provided by the primary care trusts for each locality.

Results The response rate was 73% (n = 550). Of these, 90 were not included in the final analysis due to exclusion criteria set prior to questionnaire release. This left 460 questionnaires for analysis. Eighty-five percent of respondents agreed that dentists had a responsibility to help dentally anxious patients (n = 391). Dentists were asked their reasons for not using anxiety management techniques in practice. Psychological techniques, sedation (oral, inhalation, or intravenous) and hypnosis were reported as not having been used due to the paucity of time available in practice, a shortage of confidence in using these techniques and the lack of fees available under the NHS regulations. Also, 91% reported feeling stressed when treating anxious patients. When asked about the quality of teaching they had received (undergraduate and postgraduate), 65% considered that the teaching was less than adequate in the use of psychological methods, whereas 44% indicated that they would be interested in further training in psychological methods if financial support was available.

Conclusion The need for further training in managing the dentally anxious patient is supported by dentists' lack of confidence and inadequate training in treating such patients, as determined from the results of a postal questionnaire to UK GDPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Thirty-one percent of dentate adults report feeling 'definitely anxious' in relation to dental treatment.1 Additionally, figures based on surveys such as the 1998 United Kingdom Adult Dental Health Survey,2 suggest that 64% of adults are 'nervous of some kinds of dental treatment' and 45% 'always feel anxious about going to the dentist'. The General Dental Council (GDC), in 2001, recommended that psychological anxiety management methods should be given more prominence in the undergraduate curriculum.3,4 The importance of providing effective anxiety and pain control when treating anxious dental patients has been stressed, alongside the need to formulate appropriate treatment plans when considering sedation.3,5,6 Wilson (2001) stated that the least intrusive option (ranging from behavioural management through to conscious sedation) for anxiety control should be considered before selecting general anaesthesia as the favoured method of managing anxiety towards dental treatment.6

With regard to the management of dental anxiety in general dental practice, it has been shown generally that dental practitioners are well placed to treat adults and children with mild forms of dental anxiety.7 However, little is known about the specific anxiety management techniques being used in general dental practice. Although a greater emphasis in the undergraduate dental curriculum is now placed on psychological and pharmacological issues related to the care of dental patients, the limited availability of psychological and pharmacological skills-based programmes may be exerting an effect on the range of anxiety management techniques actually used by qualified dental practitioners. Dailey et al. highlighted the limited opportunities to gain actual clinical experience in the assessment and psychological management of dental anxiety within dental schools.8 To investigate this apparent gap between psychological skills-based teaching and actual clinical practice, the present study set out to investigate the needs and potential training needs of qualified dentists in their treatment of anxious patients. This study also investigated other (pharmacological) techniques used to manage dentally anxious patients and the type of training dental practitioners wished to secure. The study design was based on a previous survey carried out with GDPs in Scotland9 and sought to replicate and compare these findings.

Aims

1) To determine the views and experiences of qualified dentists in their current use of anxiety management techniques; 2) to identify undergraduate and post-graduation training received in these techniques and perceived future training needs; 3) to replicate and compare the findings of a similar survey conducted with all primary care dentists in Scotland.

Methodology

A questionnaire was distributed by post to a sample of GDPs working across the West Midlands (n = 750) along with a covering letter describing the project and request for cooperation. Dentists were randomly selected using lists provided by the NHS primary care trusts for each locality.

The questionnaire design was of a mainly closed response format and was piloted on 20 GDPs before its full-scale release. As a result, minor adjustments were made to ensure the questionnaire was clear to understand and easy to complete, such as clarifying which type of service the question related to – National Health Service (NHS) or private. Questions covered general information such as gender, year of qualification and percentage of private and NHS treatment undertaken. The questionnaire went on to assess the types of previous training that GDPs had received in managing anxious patients and how often they used these particular anxiety management techniques. Questions also investigated the type of training which they wished to receive in the future and what funding arrangements should be in place in order to effectively treat and manage anxious patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for questionnaires were established prior to data collection. Inclusion criteria were questionnaires returned completed in their entirety and received from dentists currently employed in a primary dental care setting. The exclusion criteria were questionnaires returned incomplete. There was also an option for participants who did not wish to complete the questionnaire. All valid questionnaire data were entered into SPSS 12.0.1 (for Windows) by a single operator. Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS. Percentages and frequencies were reported for the quantitative sections of the questionnaire. Additional qualitative comments were also reported.

Results

The overall response rate was 73% (n = 550). Of these, 55 were not included in the final analysis due to exclusion criteria set prior to questionnaire release. A further 35 respondents returned the questionnaire stating they did not wish to take part in the study. This left 460 questionnaires (61%) for analysis.

The final sample comprised 66% male (n = 305) and 34% female (n = 155) dentists. The mean number of years since qualification was 18 years. Practitioners worked predominantly in mixed practices (private and NHS) (76%; n = 350), with 17% of the sample (n = 79) working solely in the NHS and a further 7% (n = 31) who were private practitioners. Fifty percent of practitioners (n = 230) worked five days per week, spending approximately 80% of their time working under NHS regulations.

Previous training

Fifty-one percent of respondents (n = 236) reported that they had received training in managing anxious dental patients during their undergraduate degree course. Training in the use of relative analgesia (RA) and intravenous sedation (IVS) was the most frequently reported. Less than half (45%; n = 205) of the sample had received postgraduate training. Of those who had received postgraduate training, 29 respondents classified themselves as NHS dentists and 16 as private dentists, with the majority coming from mixed practices (both NHS and private) (n = 160).

When asked about the quality of teaching they had received in anxiety management techniques, this was reported as being less than adequate in the use of hypnosis (75%; n = 344) and psychological techniques (65%; n = 297). Teaching in oral sedation (the term 'oral sedation' is used as an all-embracing term and covers pre-medication and oral sedation5), inhalation sedation and intravenous sedation were also considered to be less than adequate by 49% (n = 227), 47% (n = 216) and 58% (n = 265) of respondents, respectively.

Techniques used in primary care

Eighty-five percent of respondents agreed that dentists had a responsibility to help dentally anxious patients (n = 391). Practitioners were asked to report which anxiety techniques they already used in their practice (Table 1). Table 1 shows little difference between the types of techniques used in the different practices.

Dentists were asked their reasons for not using anxiety management techniques in practice. Psychological techniques, sedation (oral, inhalation, or intravenous) and hypnosis were reported as not having been used due to the lack of time available in practice, a lack of confidence in using these techniques and the lack of fees available under the NHS regulations (Table 2).

Quality of care

Dentists were also asked to assess their level of satisfaction with the quality of care which they gave dentally anxious patients under the NHS regulations. Forty-seven percent reported being 'very satisfied' to 'satisfied' (n = 218), with 53% suggesting they were 'dissatisfied' to 'very dissatisfied' with the quality of care they gave patients (n = 242). Some dentists provided open comments to illustrate the reasons for this dissatisfaction with patient care:

'Under the current arrangements you do not have time to counsel anxious patients.' (Dent 1)

'The new contract will make things even worse for anxious patients – you do not get any units of dental activity (UDAs) for anxiety management.' (Dent 2)

'The time it takes to treat these patients, I could have seen three times as many.' (Dent 3)

'I do not feel confident to deal with anxious patients.' (Dent 4)

'The NHS is not set-up to deal with anxious patients, especially now!' (Dent 5)

'The new contract [in England] does not allow the time.' (Dent 6)

'I feel practice is not the right environment for these types of techniques.' (Dent 7)

'IV sedation – the equipment is too expensive.' (Dent 8)

'I would love to use IV in practice but I cannot find any qualified staff to assist me... I have the equipment... this affects the quality of care I can give patients.' (Dent 9)

Belief statements relating to the treatment of anxious patients

Dentists were asked to agree or disagree with the following statements:

'Dentists rarely have enough time to spend with anxious patients'

Ninety percent of dentists 'agreed' to 'strongly agreed' with this statement, with only 4% 'disagreeing' to 'strongly disagreeing'. The remaining 6% remained neutral.

'Dentists enjoy helping anxious patients'

Forty-two percent of dentists 'strongly agreed' with this statement, with only 19% 'disagreeing' to 'strongly disagreeing'. The remaining 39% remained neutral.

'Dentists feel stressed when treating uncooperative patients'

Ninety-one percent of dentists 'strongly agreed' with this statement, with only 4% 'disagreeing' to 'strongly disagreeing'. The remaining 5% remained neutral.

Future training needs

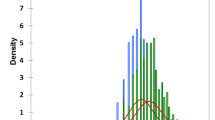

Figure 1 shows the type of training that dental practitioners would be interested in if financial support was available. A higher proportion of dentists (81%) in this study expressed a desire to have further training in psychological methods, managing LA failure (87%) and sedation (oral sedation 85%, IV 61%, inhalation sedation 74%). There were no differences between the type of practice the dentist worked in (NHS or private).

Discussion

A previous study of primary care dentists conducted in Scotland9,10 revealed that the majority of dentists felt current teaching to be 'less than adequate' and 46% believed that further training in psychological approaches would be beneficial. Furthermore, 88% of respondents stated that they did not have enough time to spend with anxious patients, with 16.4% using a psychological approach to the management of anxious dental patients.

This study mirrors the findings of the Scottish work, with dental practitioners still reporting lack of time and a lack of confidence in dealing with anxious patients. Most reported that the quality of teaching has been inadequate at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. This could be due to the lack of behavioural science teaching at the time of their undergraduate training. The GDC published its recommendations on the teaching of behavioural science and its introduction into the curriculum in 1990,4 resulting in the introduction of teaching in sedation.4 The majority of dental schools now carry out teaching in behavioural science and sedation but the amount and depth of teaching still varies between schools.10

De Jongh et al.7 suggest that general dental practice is the perfect setting in which to effectively examine and treat adults with mild forms of dental anxiety, considering that patients with moderate and severe dental anxiety may often require specialist care. The fact that over 60% of patients treated in a specialised dental anxiety clinic are able to return to their primary care provider while the remaining 40% will continue to avoid dental treatment, does not instil much confidence.7,11 It may be that the level of expertise of the dentist is important if the patient is to return for regular treatment.12 Research conducted by the Centre for Special Dental Care found that specially trained practitioners were more effective in dealing with dentally anxious patients than general practitioners.13 This suggests that appropriate training for dentists in managing dentally anxious patients is crucial.

The GDPs in this study reported feeling considerable levels of stress (91%) when dealing with anxious patients. This link between stress and anxiety has long been recognised and an increasing amount of research is being carried out in relation to levels of stress in dental practitioners. Newton et al.14 examined ways in which to reduce stress through teaching dentists to use 'an individual stress scale', and then apply ergonomic principles to control workload. For example, not attempting to do the most difficult task first thing in the morning, having adequate tea breaks, and planning and working to time. Following these principles could help dentists to manage anxious patients in a less stressful environment.14

Funding and future training

A higher proportion of dentists (81%) in this study expressed a desire to have further training in psychological methods for managing LA failure (87%) and sedation (oral sedation 85%, IV 61%, inhalation sedation 74%). In the Scottish study, only 46% of practitioners requested further training in these areas.9 However, the new NHS dental contract was also highlighted as a major barrier to taking on additional training, as practitioners reported that 'you do not get UDAs for treating anxious patients'.

It has been recognised that only a limited number of secondary care dental anxiety clinics offer training in psychological methods of anxiety management in the UK,15 in contrast to other areas of Europe and the USA. In an attempt to address the lack of accredited training at postgraduate level, a competency-based MSc course in the clinical management of dental anxiety has been developed in Scotland.15 The MSc aims to offer an appropriate level of training to qualified dentists across a range of competencies including theoretical and clinical knowledge of dental anxiety, psychological assessment, formulation and intervention skills, together with a clear framework for identifying which patients might need further, more specialist, psychological intervention.

The need for further accessible and robust training programmes at a postgraduate level has also been highlighted through a survey of dental hospitals within the UK.16 For example, Bristol Dental Hospital runs a postgraduate programme (Bristol University Open Learning Diploma – BUOLD) which covers anxiety control and sedation and receives a considerable degree of input from a clinical psychologist. The BUOLD diploma is a modular course with candidates being expected to complete three modules over a five year period. One of the modules is anxiety control and sedation. The module covers pharmacological sedation, behavioural management, cognitive therapy and hypnosis. The programme includes three study days and eight to ten written assessed assignments, which cover subjects of relevance to the topic. Practical skills are introduced with clinical attachments to the oral surgery department and candidates are encouraged to enter into the Dental Sedation Teachers Group (DSTG) and Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry (SAAD) mentoring schemes. There is a formal summative assessment at the end of the course. Also, the MSc for general practitioners at Birmingham Dental School offers the student a module in the management of dentally anxious patients, looking at both psychological and pharmacological methods of anxiety control. There are eight 4½-hour sessions covering basic anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, behavioural and cognitive behavioural therapy, pharmacological sedation, local and general anaesthesia. Candidates complete an essay and produce a presentation as part of their summative assessment. Although some practical skills are taught, there is little opportunity for clinical hands-on experience. Candidates are encouraged to enrol in the practical sedation attachment programme which is run by the NHS Trust. Table 3 lists a number of courses across the UK that offer sedation and anxiety training. This may not be exhaustive, so the Dental Sedation Teachers Group5 (DSTG) has recently convened a sub-group to address and collate a list of sedation courses across the UK.

Following the publication of the GDC document The first five years,4 all UK and Ireland dental schools have a lead member of staff who coordinates undergraduate sedation teaching. Most UK dental schools provide some exposure to intravenous and inhalational sedation techniques for their undergraduate dental students. Most, however, do not manage to achieve the minimum experience considered necessary to achieve competency, as outlined by the DSTG.

There is a shortage of opportunities for interested practitioners to get formal instruction and experience of sedation techniques throughout the country. The main problem is not with the theoretical aspects of training, but is related to access to practical, clinical teaching and experience in sedation techniques. Some options for postgraduate training are described above. Interested practitioners can study diploma and certificate courses. Societies such as DSTG and SAAD are planning to develop mentoring systems. Other institutions have attempted to provide practical clinical attachments. A set 'core course' with defined standards relating to course content, activity and experience would be advantageous to all concerned, whether they be involved in education or attempting to get further experience.

Through identifying the needs and current training requirements of qualified dental practitioners, it is hoped that further accredited postgraduate programmes can be developed to equip clinicians with the necessary skills to treat anxious dental patients using psychological approaches.

Conclusion

The need for further training in managing the dentally anxious patient is supported by dentists' lack of confidence and inadequate training. However, with the recent introduction of the new contract in England and Wales, the barrier faced by dentists and patients may become greater.

References

Walker A, Cooper I . Adult dental health survey: oral health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: The Stationary Office, 2000.

Kelly M, Steele J, Nuttall N et al. Adult dental health survey – oral health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

General Dental Council. Maintaining standards: guidance to dentists on professional and personal conduct. London: GDC, 1998, revised 2001.

General Dental Council. The first five years. London: GDC, 1990.

Dental Sedation Teachers Group. Conscious sedation in dentistry. The competent graduate. Dental Sedation Teachers Group, 2000.

Wilson N, Bernhard J, Hume W, Simpson F . Working party on the teaching of pain and anxiety control. Final report. London: GDC, 2001.

DeJongh A, Adair P, Meijerink-Anderson M . Clinical management of dental anxiety: what works for whom? Int Dent J 2005; 55: 71–79.

Dailey Y M . The use of dental anxiety questionnaires: a survey of a group of UK dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 450–453.

Adair P . A Scottish survey of primary care dental practitioners' training and education needs in managing the patient with dental anxiety. Report to Primary Care Development Fund, Scottish Executive. Edinburgh, Scottish Executive, 2003.

Meijerink-Anderson M, Adair P . Cognitive behaviour therapy training for dentists: a needs analysis. University of Dundee Dental School: BSDR, 2003.

Armfield J M, Stewart J F, Spencer A J . The vicious cycle of dental fear: exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health 2007; 7: 1.

Kvale G, Raadal M, Vika M, Johnsen B H, Skaret E, Vatnelid H, Oiama I . Treatment of dental anxiety disorders. Outcome related to DSM-IV diagnoses. Eur J Oral Sci 2002; 110: 69–74.

Moore R, Brødsgaard I . Dentists' perceived stress and its relation to perception about anxious patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29: 73–80.

Newton J T, Allen C D, Coates J, Turner A, Prior J . How to reduce the stress of general dental practice: the need for research into the effectiveness of multifaceted interventions. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 437–440.

Meijerink-Anderson M, Adair P . Training dentists to assess and treat dental anxiety using psychological interventions: a new competency-based MSc course. Clin Psychol 2004; 41: 32–35.

Hainsworth J M, Heer K, Rice A, Fairbrother K J . A survey of the current provision and input of psychological resources within dental hospitals in the UK. Unpublished report, 2006.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their thanks to Dr Pauline Adair for allowing us to reproduce the questionnaire used in the Scotland Study. This study was supported by a grant from the Clinical Trials Unit (RND), University of Birmingham.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, K., Hainsworth, J., Burke, F. et al. Evaluation of dentists' perceived needs regarding treatment of the anxious patient. Br Dent J 204, E13 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.318

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.318

This article is cited by

-

The effect of virtual reality on reducing patients’ anxiety and pain during dental implant surgery

BMC Oral Health (2024)

-

Re-introducing hypnosis to the dental profession: an evidence-based approach

BDJ Team (2021)

-

The impact of dental phobia on care planning: a vignette study

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Variation in caries treatment proposals among dentists in Norway: the best interest of the child

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2017)

-

A study to explore specific stressors and coping strategies in primary dental care practice

British Dental Journal (2016)